|

Patriarch with a Challah

Oil on Canvas, 36x36, painted 2022 Original Photograph taken – 1972 Jewish rituals and prayers are often expressions of gratitude to our Creator for the blessings in our lives. And so it is no accident that before a meal begins, (particularly at a Jewish festival, Sabbath dinner or milestone celebration) even the most non-religiously observant Jews recite the “Hamotzi” blessing over a challah bread. To elevate this ritual and honor a revered member of the family, the ‘patriarch’ (usually) is invited to stand before everyone in a hushed party room, and handle this responsibility. There are two universal ‘truths’ associated with this practice:

0 Comments

Ice Cream Dreams at St Fausten

Oil on Canvas 36x48 Painted: 2022 Original Image Taken: 1953 My parents, grandparents and extended family immigrated to Montreal after the Holocaust and rebuilt their lives with nothing but gratitude for the city, its Jewish community and Canada, the country that took them in and enabled them to start over, live in peace and security and to build a new life characterized by possibility and prosperity for themselves and generations after them, including myself and my children. This painting is inspired by a photo from the early 1950’s. My mom (still embarrassed that she was photographed wearing curlers in public) is with her brother and parents on vacation in ‘the country’ (as they call it in Quebec). After the horrors they had escaped only a few years earlier, I love how relaxed they all look, doing something so ordinary, like getting ice cream at the corner store. The symbolism of the Coca-Cola signage was not lost on me as I worked on this (Coke is a brand I associate with freedom). I truly appreciate how my family has lived in two countries (both Canada and the United States) where we are all guaranteed the right to either engage – or not engage- with our respective religions. Cheder (Hebrew School) at the DP Camp

Oil on Canvas 16x20 Painted: 2021 Original Image Taken: 1948 At 15, this was my dad’s first real experience with education. In his memoir he explains that, in all, he had 2 years of formal education in his youth: He had completed the equivalent of first grade before the Holocaust (during which time he and his family fled to the forest to hide for 19 months). When the war ended and they were in Russia, my dad had to work to help the family stay afloat. It was only when his family arrived in the DP camp in Poland, that he finally had one year of education. My dad was 16 when he finished 7th grade in 1949. The war and post-war years in Europe had robbed him of his entire youth. He never had a bar mitzvah nor did he receive an education. This painting is based off of a photo that I used to study as a child. When I was growing up, I had some understanding of the Holocaust but I couldn’t figure out why all those kids looked so ‘old’. There’s my father in the front row. He was so eager to learn and he told me that he loved that one year he had in school. (My report cards always said that I 'talked too much'. I think he would tell me this to inspire me to take my studies more seriously!). As I painted the faces of these 14 and 15 year olds I couldn’t help but compare them to my own child who is 14 today. These children struck me as so haunted and profoundly exhausted. I wondered what they had witnessed and who they had lost. Who looked after them? Did they rebuild? How did life turn out for these children? When my dad graduated law school and was called to the Bar in 1960 one of the senior lawyers at the firm where he articled remarked “it’s a long way from the forests of Poland to the halls of Osgoode Hall Law School”. The Simcha (A Joyful Occasion)

Oil on Canvas 24x36 Painted: 2020 Original Image Taken: 1974 This is a painting I made at the beginning of the 2020 Covid 19 pandemic. Like everyone, I was at home in strict lockdown, anxious about the danger of being exposed to a virus that we were only just beginning to understand and fearful of the destruction it would bring. There were no vaccines on the horizon and we were just getting acquainted with the idea of wearing masks when we went out in public. Schools were shut down, families were being kept apart, weddings and graduations were being postponed. I needed something to do to keep me calm and a distraction from my phone (where I kept close track of the daily infection rates). This was my quarantine project and it is lofty with 31 faces to paint in a single image. I was drawn to this image because this was the group in my family who started their lives together in Krakow before the Holocaust, survived the war, emigrated to Canada and built a new life. Every single person in this image was touched by the Holocaust in one way or another, (including my older sisters in the front row, all of whom were named for great-grandparents who perished). When I see these people together in their pink and purple dresses celebrating a good occasion at a simcha, after everything they’d been through, it reminded me that dark times do pass. The quarantine and this virus will eventually end and life will return. It always does. The Snowbirds

Oil on Canvas 24x36 Painted: 2020 Original Image Taken: 1975 I remember one of my earliest encounters with “FOMO” (fear of missing out). When I was in high school and we returned to class following winter break, I recall seeing a good many of the kids sporting white button-down shirts to highlight golden tans meticulously and evenly achieved at pools and beaches across Florida. I always returned to school looking as pale as ever. I spent my winter breaks at home – watching lots of TV, reading magazines and taking the occasional trip to the local ice rink. I enjoyed those breaks but how I wished I could come back to school looking like I had been somewhere exotic. I was struck by the glamor of it, wondering about fancy resorts and colorful drinks garnished with cocktail umbrellas. Most of my friends, it turns out, were visiting their ‘snowbird grandparents’. These were older Jews – often Holocaust survivors – who managed to save enough money to buy a modest apartment at places like “Century Village” and spend their retirement years in sunny Florida. These folks would leave the cold and snowy north from Thanksgiving until Pesach enjoying warm weather, good programing, fun activities and socializing. For two weeks every December, bubbies and zeidis from Miami Beach to Fort Lauderdale endured the disruption to the peace and quiet at their community pools, and ‘shepped nachas’ (felt pride) while hosting their grandchildren. Oil on Canvas 9x12

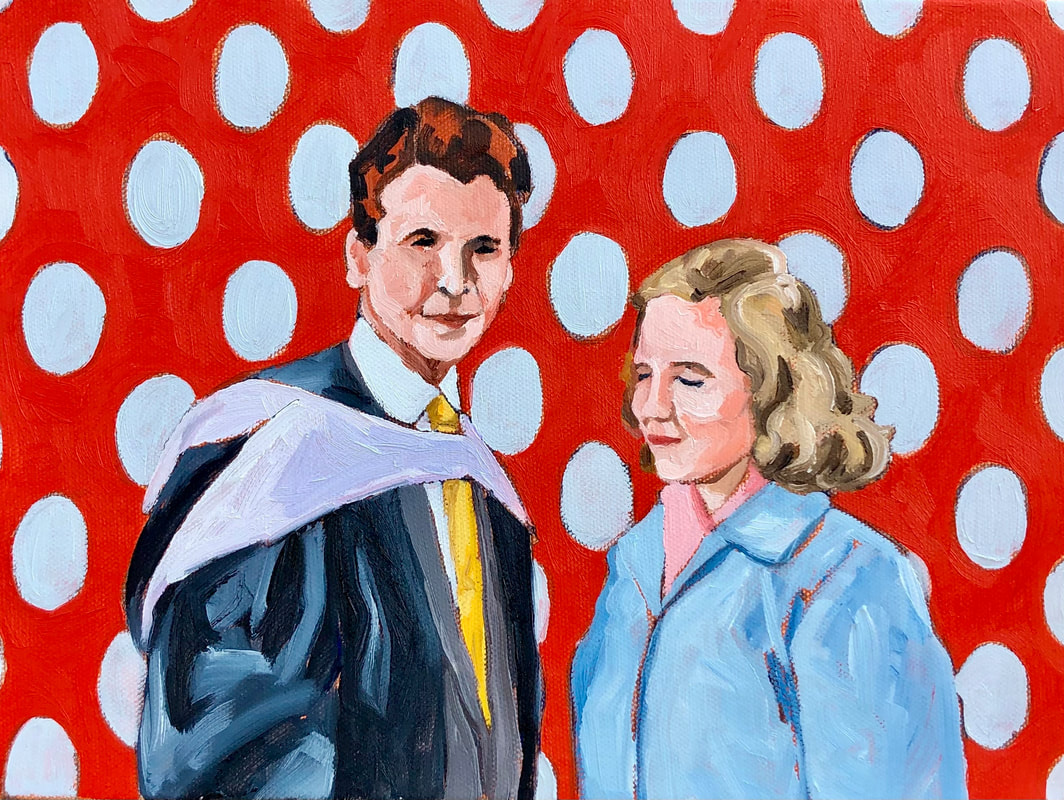

Painted: 2021 Original Image Taken: 1956 When my family immigrated to Canada in 1949 after the Holocaust, there were so many obstacles to overcome. Every success was monumental. What could be better than passing the high school matriculation exams and then getting a degree and attending law school after virtually missing a lifetime of education during the war years and the time spent in DP (Displaced Persons) camps? When my dad graduated from Sir George William University (now Concordia University) it wasn't just for him. There were so many people who were invested in this achievement, especially those who hid in the forest with him for 19 months during the war. But the person who really deserves a special mention was a teacher named Miss Mitchell. Shortly after my dad immigrated to Canada and was learning to speak English he happened upon a a tutor who was helping a boy who lived in his flat. Miss Mitchell wasn't wanting to take on any more students but she saw something special in my dad and decided to help him get ready to take the grade 11 matriculation exams. Realizing that he was a refugee and funds were tight, she refused to take her full pay. Here is how my father honored Miss Mitchell in his memoir: "In late summer 1953 I learned Miss Mitchell was not well and that she couldn't continue tutoring and guiding me anymore. I soon wrote some 7 or 8 exams and passed. I was admitted to Sir George William University and I personally wanted to tell Miss Mitchell. I found out that she was now at the Royal Victoria Hospital. When I came there, her brother told me she was dying of cancer and that the diagnosis was the reason for her relatively early retirement. I was allowed to see her. She was alert and I told her the good news. I gave her my hand and she squeezed it hard. She died a week later. Amazing how she did not let on over all those months that she tutored me! The vehicle of this lady's generosity carried me through the roughest terrain on my journey to where I wanted to go" 1950 Ladies Auxiliary Tea - United Jewish Welfare Fund

Oil on Canvas 16x20 Painted: 2021 Original Image Taken: 1950 When my parents immigrated to Montreal after the Holocaust, they (like so many survivors) were absorbed by the established Jewish community. I never really thought about the task of welcoming thousands of refugees, many (if not most) of whom arrived in Canada traumatized by the events of the second world war. How did the established Jewish community prepare to help these people whose needs were so profound? I have nothing but gratitude for the types of women, like those pictured here, who came together to fundraise, collect material donations, volunteer at clothing banks and provide scholarships to young refugees who couldn’t afford tuition for Jewish summer camps and schools. I am certain that in the early 1950’s, my family benefited from these efforts and generosity. In many ways, however, Montreal’s Jewish community (like so many established Jewish communities in North America) was strained by the sudden influx of Jews from the ‘old country’. While united by a common code of religious practice and customs, these Jews couldn’t have been more different from each other. It was nearly impossible for the survivors to talk about the horrors inflicted by the Nazis, and frankly, the established community was not all that interested in hearing about it (at least not back then). It was beyond overwhelming for both sides. Furthermore, the arrival of the refugees altered the landscape of the established Jewish community and thus brought a sense of insecurity for them: would the very presence of these immigrants threaten the equilibrium and tentative acceptance the ‘Canadian Jews’ had worked so hard to achieve, living quietly in suburbs alongside the larger Gentile Canadian community? The Canadian Jews had their own history. They were the descendants of parents and grandparents who fled the pogroms in Russia. At the turn of the century, these people arrived on boats only to be greeted by a Canadian society that had restricted neighborhoods, hotels and beaches, quotas for higher education and outright disdain for the Jewish immigrants and their ways. It took 50 years for the Jews in Canada to respond to this brand of anti-Semitism and build their own parallel institutions, like the Jewish General Hospital, social clubs, the YMHA and various Jewish Community Centers. As these early Canadian Jews amassed wealth, many wanted to simply ‘fit in’- to look and act like their Gentile neighbors and deflect any negative attention. The presence of the Holocaust survivors must have reminded them of their grandparents and the obstacles they overcame. The Canadian Jews definitely cared about the well-being of the Holocaust survivors and took responsibility to help them. But they didn’t always want to socialize with or live in the same neighborhoods as the refugees. Perhaps it was too painful, or it was snobbery, or maybe a little of both. Time is a funny thing though. Within a generation, the children and grandchildren of the refugees and those of the ‘established’ Canadian Jews almost immediately became indistinguishable. I know this firsthand. Most of my friends descended from the ‘established’ Canadian Jewish community. We freely and happily socialized in each other’s homes, we went to the same summer camps, high schools and universities, attended the same parties, dated each other, got married and built life-long friendships together. For better or for worse, this pattern repeated itself when the influx of Russian Jews arrived in Canada and the US in the early 1990’s. Newcomers at Fletcher's Field

Oil on Canvas 24x36 Painted: 2021 Original Image Taken: 1949 My father always told me that he never had a childhood. The hardships of the Holocaust forced him to grow up fast and become an adult literally overnight. In 1949, he was only 16 that first summer in Canada but his ‘social life’ mostly included people much older than him. As Holocaust survivors these people found community with each other. They were hollowed out by atrocities of the war and together they could just be themselves at gatherings like the one pictured here. Fletcher’s Field was a park right across the street from the Jewish Immigrant Aid Services office in Montreal. The park offered green spaces for newcomers to gather, search for ‘landsmen’ and share stories about adapting to the strange new culture they were trying to understand and find their place in. These people did not want to be at the receiving end of community assistance. They just wanted to get on with life, rebuild their families and contribute to the country that had taken them in. Family Reunion at Val Morin

Oil on Canvas 24x30 Painted: 2021 Original Image Taken: 1953 In the early 1950’s, just a few short years after my mom immigrated to Montreal, she and her family were often invited to the ‘country homes’ of distant cousins who had arrived in Canada a generation before them. How awkward these reunions must have been. Well-intended relatives wanted spark friendships amongst teenaged cousins whose lives and experiences were so very different. The suffering of the Holocaust hovered over these gatherings but nobody wanted to talk about it. The newcomers tried their best to fit in with the ‘Canadians’ but I suspect it never really felt natural for anyone. Women’s Division Oil on Canvas 16x20 Painted: 2020 Original Image Taken: 1975 One of the things I love most about being Jewish is probably the very thing that I have always taken for granted: the organized Jewish community and the infrastructure that supports it. At any stage of my life, whether I was a new mom searching for camaraderie through ‘Tot Shabbat’ classes, or finding a kosher caterer for my wedding, or joining the JCC (Jewish Community Center) to take an aerobics class, I have always been able to connect to the right organization and seamlessly have my Jewish needs met. The organized Jewish community has never let me down. Having worked as a professional in Jewish communal service for many years I also know that the Jewish community is there to step in and support its most vulnerable members with high quality assistance that is culturally sensitive in every way. “From the cradle to the grave”, the Jewish community is there when you need it. But who makes it happen? Women like the ones pictured here are often at the heart of community fundraising efforts. One of my dear friends recounted memories of her mom’s tireless devotion to fundraising for her local Jewish Federation. Shawna told me that her mother, a gifted philanthropist, approached the task with flair and a sense of occasion to motivate her women friends to come to her living room and get involved. Through personalized note-writing campaigns armies of women raised funds for anything from feeding the hungry to opening a new wing at the senior citizen’s memory care facility. Shawna remembers the preparations that her mother organized in advance of these meetings: the wall-to-wall carpeting was freshly vacuumed such that you would see tracks from the Electrolux; the silver was polished to a shine and baked goods (that had been frozen in tins for weeks) were laid out on the good china. Hair appointments and elegant dresses with the smell of different perfumes wafting through the house were all a part of the effort. But in the end, “community” was as the forefront of these meetings where women gathered for socializing and hard work to plan galas, special events and auctions that raised the funds needed to achieve their goals. |